People

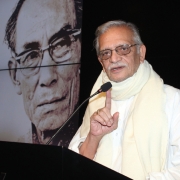

He was recently awarded the Dada Saheb Phalke Award, the highest award in Indian cinema. But legendary writer Gulzar’s legacy transcends the confines of filmdom. A recorder of our times, the versatile writer-director-storyteller shares some lesser known nuggets of his life with Deepa Narayanan

His songs have long played on our lips. Gulzar, born Sampooran Singh Kalra, may have captured the public imagination essentially owing to his association with the film industry. But the prolific writer draws from his reservoir of experiences of a childhood in Deena—a village in present-day Pakistan—where he was born to Makhan Singh Kalra and Sujan Kaur; the Partition; initial years in Delhi; his deep connect with Bengali culture; and years of struggle as a poet in Mumbai. Decades later, the pain of Partition still smolders in Raavi Paar And Other Stories in which he writes, Mera watan jo udhar rah gaya aur mera mulk jo idhar hain, dono mein main batt gaya (My motherland, which I had to leave behind on that side, and my home where I now live, on this side, so divided do I feel in between these). Talking about the influence of life on literature, he tells us, “When literature starts relating to life, you just begin transcribing it from your own life.”

Even as he modestly admits that he is trying to keep pace with changing times, Gulzar has been far ahead of his times, as evident in his thoughts and works. Credited with pioneering Triveni, poems with three-lined stanzas, Gulzar has also tackled social issues through films like Maachis (terrorism), Mausam (prostitution), and Hu Tu Tu (corruption). He has also been an avid advocate of children’s literature, closely associated with the Karadi Tales, and other stories including the ‘Bosky Series’, a collection of stories he wrote and presented to daughter Meghna (her nickname is Bosky) on each of her birthdays as she was growing up. His lyrics for the popular television series Jungle Book, “Jungle, jungle pata chala hai, chaddi pehenke phool khile hain,” become an anthem of sorts for children, as did Lakdi ki kaathi from the movie Masoom. In fact, such is the power of his pen that Humko mann ki shakti dena, a song he penned for the film Guddi, still reverberates in the prayer halls of many schools.

While the accomplishments of Gulzar, who recently turned 80, have made him a celebrity, his distaste for the limelight and its encroachment into his personal life have made him draw a thin but perceptible line. When we request an interview with the writer-poet a few months after he is honoured with the 2013 Dada Saheb Phalke Award for Lifetime Achievement, we can sense his cautiousness to yet another replay of questions coming his way—about his career and life. We are given 45 minutes, a timeframe we are painfully aware is unrealistically short to meet a man this legendary, about a life this enriching. Hoping not to miss out on any of those granted minutes, we arrive at Boskyana, his residence-cum-office in one of the lush green suburbs of Mumbai—named after his daughter—15 minutes earlier than scheduled. Countless Filmfare and National Awards, the 2002 Sahitya Akademi Award, the Padma Bhushan in 2004 and the Academy Award for best original song Jai ho with A R Rahman at the 81st Oscars in 2009, all adorn his shelf. Even as we are shown in his office, Gulzar sahib appears in his trademark crisp white cotton kurta pyjama, smiling, his eyes glowing with warmth and anticipation of what new he may find during this conversation. His only request is not to ask oft-repeated questions. As we settle into his study, he offers us tea, and soon we begin the interview with questions that have long played on our minds. Thus begins a candid and emotional conversation that goes way beyond the stipulated time we have been allotted.

EXCERPTS FROM THE INTERVIEW

You seem to be particular about your boundaries. When did you feel the need to build them?

Really? Do I seem like I have boundaries around me? That is interesting! I have never done that deliberately—denying someone entry into my life. I have only welcomed others into my life. Probably the boundaries you are referring to are the ones I have created for myself, not venturing into areas that I’m not too comfortable with. As I understood my strengths and weaknesses, and became aware about what I’m comfortable indulging in, I drew these lines around me, defining what I should be doing and should not be doing. When you know yourself like that, those ‘boundaries’ travel with you. But to get there, I think it is important to just be yourself. And when you stay true to yourself, you start knowing even others a little better.

Not many people live by that principle.

Of course, I realise it is not easy to get there—to define one’s likes and dislikes and stick by them without putting on a façade for someone else. I think it all depends on the circumstances you have grown up in, your family and friends. It may not be easy to live the way you want to. But I believe it is easier to just be yourself without pretending to be someone else.

When was this need to express yourself born?

I don’t recall any particular point or moment. Since childhood, all of us are recording things that are happening around us. If I were to use an analogy, it would be of a covered vessel kept on coal, with water in it. When the water starts boiling, at one point the steam starts shaking the lid, making it clang against the vessel. I’m like that dhakkan [lid]; I started clanging so violently that I had to let the steam out. [Laughs.]

When did you start writing?

I started writing while I was still in school. As I mentioned, there was this strong urge to express myself. I could never memorise the lessons taught at school; I have never really bothered about marks, which is also why I never graduated. However, I soon realised that what was narrated in the textbooks actually related to life. And, when I understood that, those lessons went beyond the written word for me. For instance, I remember reading Idgah, a short story by Munshi Premchand about a boy who watches his grandmother using her bare hands to pick up roti from the hot tawa, burning her hands in the process. During Id, the boy asks his granny for some money as Idi. She gives him some pennies she has kept aside. But he asks for more. Assuming that he wants to sit on the rides at the fair, she pulls out a couple of pennies more, telling him to have fun at the fair. In the evening when the boy is back, she asks him about the rides, and is surprised when he tells her that he sat on none. When she rebukes him about what he may have done with the money, he gives her a pair of tongs, so that she doesn’t ever have to burn her hands while making roti. I could relate to the story as my mother too used to make roti in the tandoor, burning her hands every time she put them in or took them out. So a story that was meant for children to write essays on was more than mere words for me; it was something I could relate to. Gradually, I started reading literature meant for my older brothers. I remember taking Bal-E-Jabreel by Allam Iqbal, my older brother’s textbook, and not returning it. It’s only recently that I told him about it; he was under the impression that he had lost it somewhere else. [Laughs.] Literature and books became a passion with me and soon I started writing poetry.

You seem to be totally fascinated with poetry compared to other forms of literature.

Yes, my passion for writing initially manifested as poetry. Though I love telling stories and have written some short stories, my primary passion has been poetry. But I am not sure I can explain why I prefer poetry to other forms of expression. It is like asking why you are wearing a particular dress. You may not have an answer to that, would you? [Smiles.]

Your father didn’t approve of your engagement with literature.

That was the case with every parent back then. They didn’t want their children to eke out a living from literature because, as a profession, it wasn’t rewarding enough. My father used to say, “Shayari-waayari karnee toh theekh hain; gurudware mein paddh lo yah kuch. Par kaam kya karoge?” (If you want to render a poem or two at a gathering or in gurdwaras, it’s fine. But, finally, what profession are you going to take up?) For my father, art didn’t make sense economically. But things have changed now, and writers are being looked up to; people even come to take interviews of shayar.

Not every writer is interviewed, Gulzar sahib.

[Smiles warmly.] My father wanted me to learn something more so I would get a stable income. His concern was understandable. I loved referring to my father as Abbu. [Chokes.] In a recent book on me, In The Company of a Poet, written by Nasreen Munni Kabir, I have dedicated an Urdu verse to my Abbu. (Given below is the English translation.)

Father, There is much to say that is left unsaid

If you were here, I would speak

You were so despondent on my account

Fearing my poetry would drown mesome day

I am still afloat, Father

No longer have I the desire to return to shore,

The shore you left so many years ago.

Did he get to see your success?

He suspected that I was on to something. If my poems or stories were published, he carried them around, proudly showing them to his friends. Even if he did not broach the topic on his own with anybody, I could see he was proud. But back then, I was still unknown and a struggler. Though my works were getting published, I knew that my father still worried about me.

In fact, he would say, “Yeh bhaaiyon se udhhaar maangega aur langhar mein khaana khaayega.” (He is going to borrow from his brothers and eat at the langhar served in gurdwara.) He did not see my success. He has only seen my struggle. [Chokes again.]

Whether it is Mora gora ang lai le or Chaiyya chaiyya; Bunty Aur Bubli or Omkara, your lyrics resonate with the generation you are addressing. Is this born out of your need to ‘earn your bread’?

Honestly, my motivation has never been earning my bread. Though I struggled, I was never consumed by the fear of failure. In fact, no one starves to death because you don’t earn enough by writing. You can always eat less. Of course, you can earn enough to live, even as a labourer. I wanted to be a writer. That was my only passion. I have even done some silly things. I remember there was a book of short stories by Guy de Maupassant that I read enthusiastically. I wanted to see how my name would look on the cover. So, I stuck my name over Maupassant’s name. Years later, my daughter Meghna saw it and asked me about it. When I told her what I had done, she took that book from me. She has mentioned this in her book Because He Is, with a picture of that book as it is now. That is how badly I wanted to be a writer!

But wasn’t it through films that you earned your bread initially?

I was working at a motor garage when I was pushed into writing a song for a movie. I had no interest in the film industry and was happy just reading and writing poetry. I was close to Shailendra, the lyricist, whom I had known since my stint with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), Progressive Writers’ Association (PWA) and from my trade union days. He had a tiff with Sachin da [Sachin Dev Burman], the music composer of Bandini, who was on the lookout for another lyricist. So, I wrote my first song, Mora gora ang lai le. Afterwards, Bimal Roy, the director of the film, came looking for me. He had heard from someone that I had studied Bengali only to read Rabindranath Tagore. Bimal da must have seen something in me—either talent or hard work. He said, ‘I know you don’t like to write for movies, but come and join me for a director’s meeting; you will like it. No matter what you do, please don’t go back to that motor garage. Don’t waste your life there.’ That was a very emotional moment for me and I broke down. Thus, I got into writing for films, and here I am. However, books have remained my enduring passion. I did films for a while and then came back to my books.

That disconnect from films is evident in your works.

It is not exactly any disconnect. Besides writing lyrics, I have made verbose films, the kind writers tend to make. For instance, Mere Apne, Parichay, Koshish and Aandhi were all a writer’s films. It is after Kitaab that I started learning the visual medium and its language. That is why my later films like Maachis, Kitaab, Mausam and Hu Tu Tu were all filmmaker’s films. But I was beginning to miss the writer in me, and all that I wanted to do was write. I also wanted to write for children. Do you know that there is hardly any literature in India for children other than in Bangla, Marathi and Malayalam? There was a big world outside films that I wanted to be a part of. I did not really care about money or fame, and I had nobody to prove anything to. Films were not the anchor for me, books were. They remained with me, and I came back to them.

What are you working on right now?

I am currently working on two volumes of Tagore that I have translated from Bangla. I hope I will be able to get the nuances right. Tagore’s own English translations are not as good as his Bangla poems; he used to edit his pieces rather drastically. I have translated Tagore’s poems for children into English because I want children all over India to read him. There is so much that needs to be done. [Pointing to his table with a pile of books and stacks of files] This is a pile of 400 to 500 poems from over 30 Indian languages by different poets, including those from Nagaland, Assam and Manipur. I’m selecting 365 poems from these to compile into a book called A Poem A Day.

So yes, films have brought me a lot of fame, and there is a sense of gratitude but there is so much more to life beyond. When you start exploring life around you, you will realise the vastness of the universe and the cosmos. I write songs for a couple of reasons. For one, I love poetry, and songs let me indulge in that. Second, with all of my qualifications of an Intermediate failure, nobody will employ me for even ₹ 1,500. [Laughs.] So the songs bring home the money. Beyond that, the film industry is only one medium and it takes away all your time.

The film industry is known to be cutthroat, breaking hearts and killing spirits. But your lyrics and poetry still ring with a sense of freshness.

No matter what your creations, they reflect your own personality. That is why the renditions of Kishori Amonkar and Pandit Bhim Sen Joshi will be different even if they sing the same raag on the same stage the same evening. On the same lines, cynicism will show in your works only if it exists in you.

You have been an avid advocate of children’s literature and have published books since the early 2000s, beginning with the Bosky series for children. How is writing for children different?

My earlier books for children were a process of learning and understanding them. When we write for adults, we communicate in one standard language. So it is easier to write for adults than kids. When it comes to children, you need to communicate differently with different age groups. You cannot tell a three year-old stories meant for a 10 year-old and vice versa. But most writers think it is easy writing for them and keep making the mistake of speaking to kids in a static tone they use for adults. Also, you have to first indulge children before you learn how to write for them. It is sad that a major language like Hindi hardly produces children’s literature. There is nothing in Hindi except translations from Panchatantra and other languages. That can hardly be classified as children’s literature. Children’s stories need to be based in one’s own time.

Have you ever hit a writer’s block?

Everybody hits a block, even a potter. Sometimes his fingers don’t move. In fact, some days even a cow doesn’t give milk. There is nothing to worry if you can’t write or if you have forgotten a line that you thought of. But you have plenty to worry about if you have forgotten where you have left your wallet! [Laughs.] My advice to writers would be to stay real and not take oneself so seriously. Just because you have become a writer, you aren’t meant to be flying around! As a writer, I am just as professional as a plumber is. You have to play your role in society. Through writing, you record the times you live in. You are a historian and the aesthetics and human relations you are creating make you as indispensable to society as a plumber. A writer is not a privileged being. In fact, I believe a plumber is more practical and useful to society than a writer. It is important to create utility through your writing for the society in which you are living.

DIRECTOR’S CUT

Mere Apne (1971)

Parichay (1972)

Koshish (1972)

Achanak (1973)

Aandhi (1975)

Mausam (1975)

Khushboo (1975)

Kinara (1977)

Meera (1979)

Angoor (1981)

Namkeen (1982)

Lekin (1990)

Maachis (1996)

Hu Tu Tu (1999)

CHART BUSTERS

- Mora gora ang laiye le – Bandini (1968)

- Hamne dekhi hai un aankhon ki – Khamoshi (1969)

- Wo shaam kuchh ajeeb thi – Khamoshi (1969)

- Maine tere liye hi – Anand (1970)

- Bole re papihara – Guddi (1971)

- Hum se watan hamara aur watan se hum – Koshish (1972)

- Beete naa bitaayee raina – Parichay (1972)

- Musafir hoon yaaron – Parichay (1972)

- Dil dhoondta hai phir wohi – Mausam (1975)

- Maajhi re – Khushboo (1975)

- Tum aa gaye ho noor aa gaya hai – Aandhi (1975)

- Tere bina zindagi se koi shikwa toh nahi – Aandhi (1975)

- Tere bina jeeya jaaye na – Ghar (1977)

- Aaj kal paaon zamin par nahi – Ghar (1977)

- Thoda hai thode ki zarurat hai – Khatta-Meetha (1977)

- Naam gum jaaega – Kinara (1977)

- Tujhse naaraz nahi zindagi – Masoom (1983)

- Lakdi ki kaathi – Masoom (1983)

- Surmai ankhiyo me – Sadma (1983)

- Mera kuchh saaman tumhare paas – Ijaazat (1988)

- Yaara seeli seeli birha ki raat – Lekin (1991)

- Dil hum hum kare – Rudaali (1993)

- Chappa chappa charkha chale – Maachis (1996)

- Goli maar bheje me – Satya (1998)

- Dil se re – Dil Se (1998)

- Chhaiya chhaiya – Dil Se (1998)

- Chhai chhappa chhai – Hu Tu Tu (1999)

- Tu hawa hai fiza hai – Fiza (2000)

- Aaja gufaaon me – Aks (2001)

- Saathiya – Saathiya (2003)

- Dhadak dhadak – Bunty Aur Babli (2005)

- Kajra re – Bunty Aur Babli (2005)

- Beedi jalaile – Omkara (2006)

- Barso re – Guru (2007)

- Jai ho – Slumdog Millionaire (2009)

- Dhan te nan – Kaminey (2009)

- Dil to bachcha hai – Ishqiya (2010)

- Yaaram – Ek Thi Daayan (2013)

Photo: Amit Gaur & Fotocorp Featured in Harmony — Celebrate Age Magazine October 2014

you may also like to read

-

For the love of Sanskrit

During her 60s, if you had told Sushila A that she would be securing a doctorate in Sanskrit in the….

-

Style sensation

Meet Instagram star Moon Lin Cocking a snook at ageism, this nonagenarian Taiwanese woman is slaying street fashion like….

-

Beauty and her beast

Meet Instagram star Linda Rodin Most beauty and style influencers on Instagram hope to launch their beauty line someday…..

-

Cooking up a storm!

Meet Instagram star Shanthi Ramachandran In today’s web-fuelled world, you can now get recipes for your favourite dishes at….